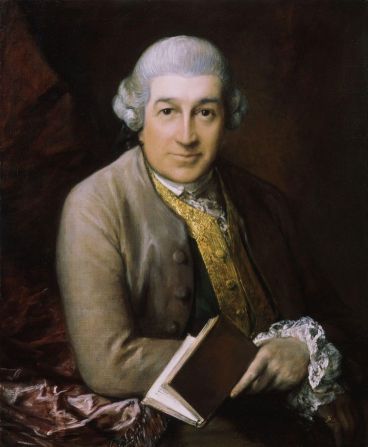

Portrait of David Garrick by Thomas Gainsborough, 1770 (National Portrait Gallery, London).

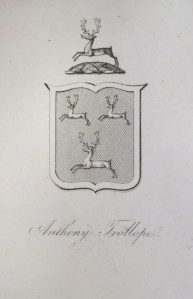

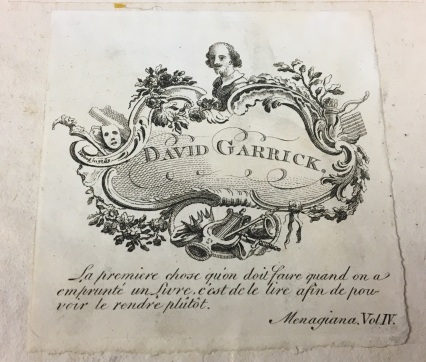

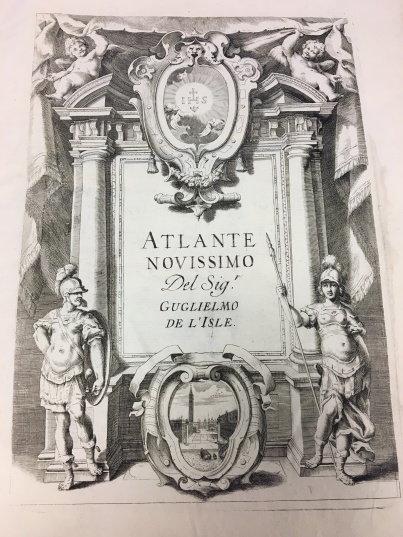

As I was beginning to work on a two-volume atlas from the Cavagna Collection printed in Venice between 1740 and 1750, I noticed from the rather rudimentary catalog record that a second copy was listed as containing the bookplate of David Garrick (1717-1779), the most famous Shakespearean actor of the eighteenth-century, whose legacy is still very much present today – there are many Garrick Theatres in cities around the world, as well as the Garrick Club, founded in 1831 in London’s Covent Garden. This connection seemed almost too good to be true, so I set out in to the vault to inspect the item for myself. To my surprise, there had been no mistake; I opened the front cover of each volume to see Garrick’s bookplate, engraved by John Wood, complete with a bust of Shakespeare and other theatrical paraphernalia.

Garrick’s bookplate. The quotation underneath is from the French author Gilles Menage (1613-1692), and roughly translates as, “The first thing that you must do when you have borrowed a book is to read it so that you may soon be able to return it.”

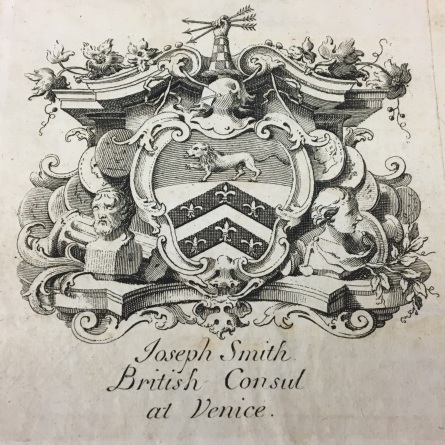

Above Garrick’s ex-libris, however, was another, this time announcing the volumes as having belonged to “Joseph Smith, British consul at Venice.” Though this name did not ring a bell with me, a few minutes’ research revealed Joseph Smith (circa 1682-1770) to have been one of the most celebrated bibliophiles of his generation, responsible for contributing to what would become the King’s Library at the British Museum, now in today’s British Library. First travelling to Venice around 1700 as a merchant banker, Smith held the position of British consul to Venice from 1744 to 1760, and died in that city in 1770.

Smith’s bookplate, engraved by Antonio Visentini.

King George III had come to the throne in 1760, only to find the Royal Library more or less depleted, its contents, dating back to the reign of Henry VII, having been donated by his predecessor, George II, to the newly-founded British Museum. In 1762, the cash-strapped Smith sold the king his massive collection of important books, prints, and paintings, acquired over his many decades as a collector, although his urge to amass more did not stop there. In fact, upon his death ten years later, he had so many books in his possession that it took nearly two weeks to auction off that second library.

It seems that this copy of Atlante novissimo must have been a part of Smith’s second library, either at Venice or Mogliano, his summer house, though I have been unable to locate it in any of the catalogues of his collection assembled after the sale to the crown in 1762. Some time in the next few years it came in to Garrick’s possession, though he would not have had long to enjoy it, as he would die in 1779. Though best known as an actor and theater manager, Garrick was an avid book collector, amassing over 3000 volumes, and he is especially revered today as a collector and thus early preserver of many items relating to Shakespeare and his seventeenth- and eighteenth-century legacy. Oddly, our Atlante novissimo is not to listed in the 1823 sale catalogue of his library.

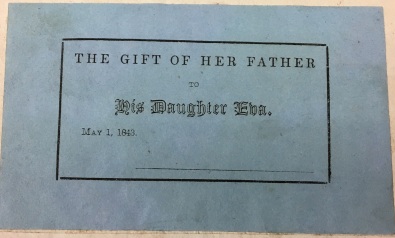

A third bookplate was placed above Smith’s in the first volume, and bears the following text: “The gift of her father to his daughter Eva, May 1, 1843.” The identity of Eva is a mystery, as Garrick had no children, and I was unable to locate any other book bearing this same bookplate anywhere online. (Any leads in this area would be greatly appreciated.) The University of Illinois acquired this copy in 1941.

We are excited to announce the rediscovery of this item’s extraordinary provenance, even more so as the tercentenary of Garrick’s birth was only last month. The Victoria and Albert Museum celebrated this occasion with an exhibition of its own, “David Garrick: Book Collector,” showing off a selection of the Garrick items owned by nineteenth-century Shakespeare scholar Alexander Dyce, and subsequently donated to the museum. TAWB

For more information about Smith’s collection, please see

Morrison, Stuart. “Records of a Bibliophile: The catalogues of consul Joseph Smith and some aspects of his collecting.” The Book Collector, 43:1 (Spring 1994), 27-58.

![Inscription reads: “[H]or bouk / bot at London”](https://nonsolusblog.files.wordpress.com/2013/10/urania014.jpg?w=300&h=214)