In late 1544, Henry VIII’s forces were defending the English possession of Boulogne in a series of brutal battles against the French as part of the Italian War (1542-1546). They were aided by Giovacchino da Coniano, a sergeant-major in charge of the Italians fighting on the side of the English. The king had been present in France earlier in the conflict, but he later returned to England, leaving the dukes of Norfolk and Suffolk to lead his troops in defending Boulogne. The two leaders disobeyed Henry’s orders, leaving several thousand men at Boulogne and withdrawing the remainder of the army to Calais. The French forces, however, were eventually beaten back from Boulogne, gaining victory for the English. Although an otherwise minor figure in military history, da Coniano left behind a manuscript containing diagrams of battle formations employed during his time in France which would eventually come in to the hands of Girolamo Maggi, who would publish a portion of it two decades later.

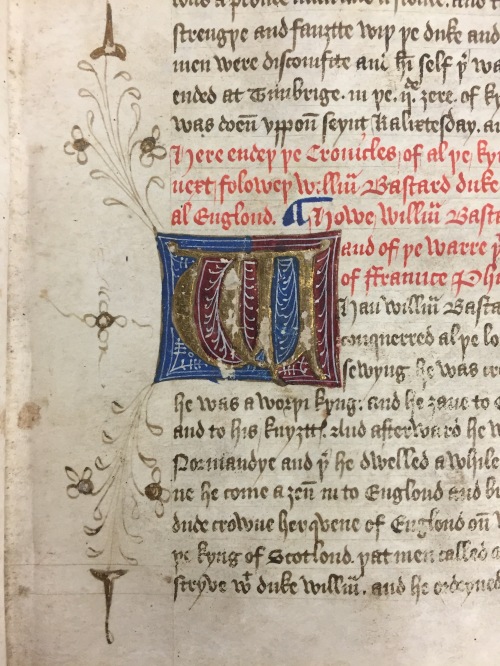

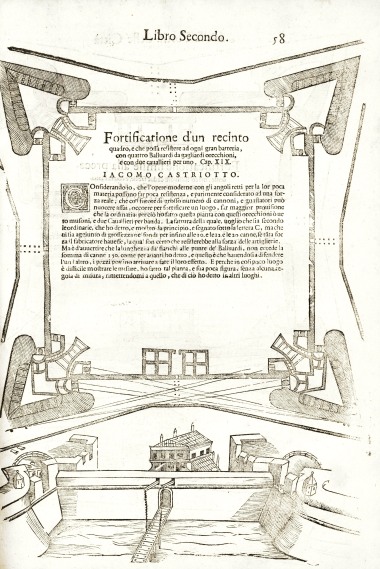

Maggi (circa 1523-1572) was born at Anghiari, near Arezzo in Tuscany. He studied at Perugia and Pisa, where he developed a keen interest in ancient languages and architecture, as well as Roman law. He was also a student of old sarcophagi and funerary monuments, and used his expertise to argue against the then-common belief that giants had once roamed the earth. His first work, a poem on the war being fought by the Italians in Flanders, was published in 1551. In the same year, he completed the manuscript of his Ingegni et invenzioni militari, a work on military engineering, and dedicated it to Cosimo de’ Medici. Maggi’s Della fortificatione delle città (On the fortification of cities), was printed by Rutilio Borgominiero in Venice in 1564. In reality a compendium of works on fortification and defense, the volume contains five works: (1) the eponymous treatise, actually a coproduction between Maggi and Jacopo Fusti Castriotto, a military engineer who had died in 1563; (2) a discourse by Maggi on fortifying barracks; (3) a work by Francesco Montemellino on the fortification of the Borgo district of Rome; (4) da Coniano’s treatise on military logistics and battle formations; (5) and a work by Castriotto on the fortresses of France. The Rare Book & Manuscript Library holds a later edition of the Della fortificatione in its Cavagna Collection, printed in Venice by Camillo Borgominiero, brother of Rutilio, in 1584.

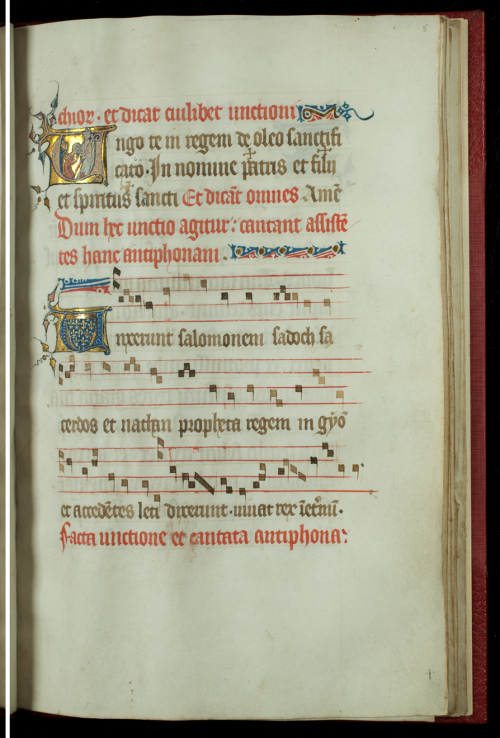

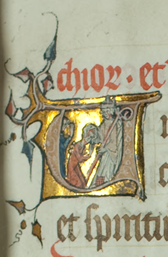

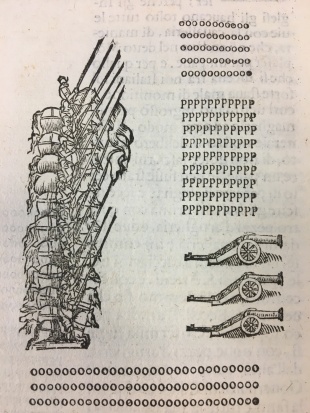

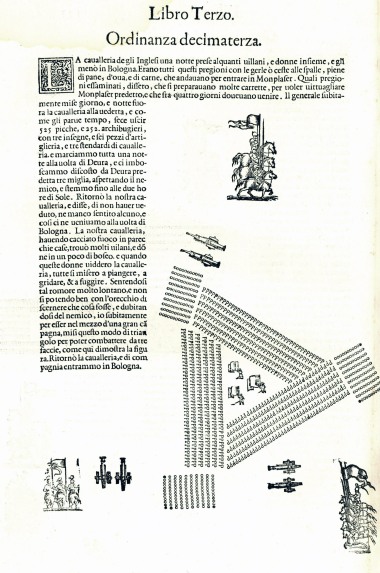

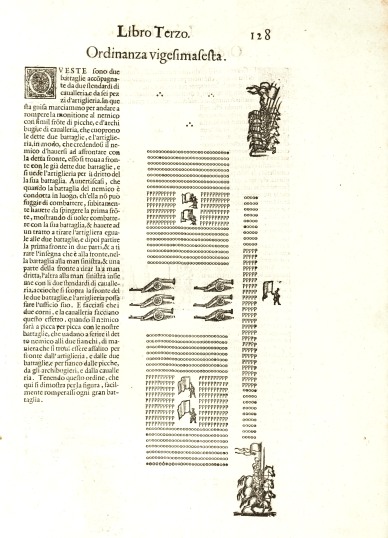

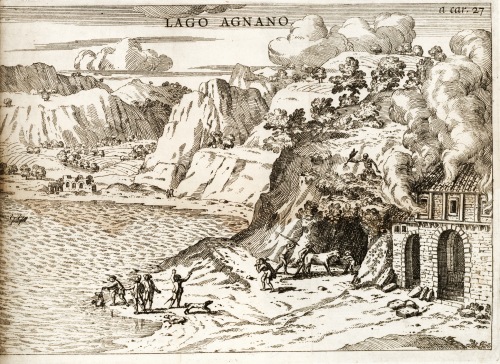

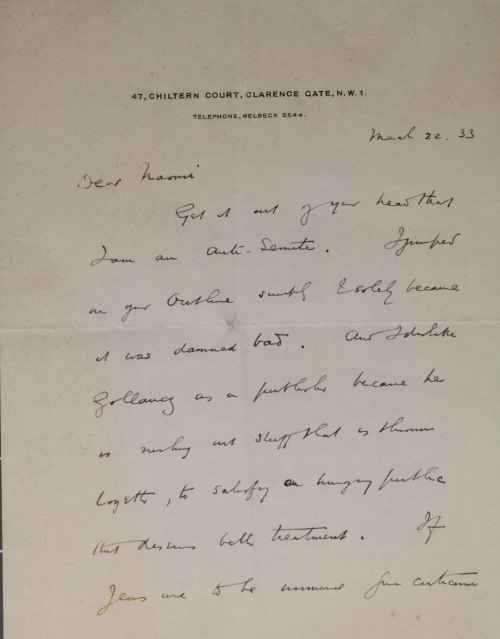

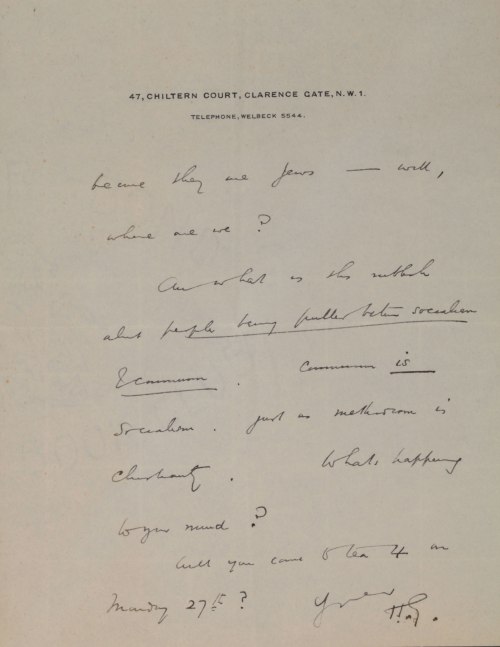

Novel illustrations accompany Coniano’s text, made up of combinations of small woodcut elements, depicting cannons, standard-bearers, and other military figures, and individual letters, each representing a different kind of soldier: o stands for archibugieri (musketeers); a for archieri (archers); r for acabie or ronche (halberdiers); p for picchieri (pikemen); and C for cavalli (cavalry). These formations must have challenged the typesetter, as they sometimes involve oblique orientations, the tight packing of type, and the careful layout of various sections of “troops.” (Even more burdened by this system of notation is modern optical character recognition, or OCR, technology, whose limits are revealed in some online versions of the text.) Other portions of the compendium are also visually rich. Maggi and Castriotto’s treatise has scores of illustrations of fortification methods, many containing text within the “frame” of the woodcut itself.

A note to the reader appended by Maggi to the end of the work admits that the text is incomplete, but that he has been informed by a Venetian friend that the text in its entirety would cover such topics as defensive trenches, tunnels, bridges, and firearms. Maggi ends with an expression of hope that these lost passages could be recovered and shared with the world. As far as is known, the complete text remains lost to history.

Maggi’s life ended in a dramatic fashion. Around 1570, he became a military engineer to the Republic of Venice. Soon afterwards, he went to Cyprus, where he acted as a judge and advised on the defenses of Famagusta, which was held by Venice. After the Turks laid siege to the city, Maggi was captured, enslaved, and taken to Constantinople. He was made to work on a merchant ship and later wrote two further works while in prison, without the aid of a consulting library. These were the De tintinnabulis, on bells, and the De equuleo, on an instrument of torture similar to the rack. These works attracted the attention of the French and Italian ambassadors to the Ottoman Empire, who were impressed by Maggi and sought to have him released. As Maggi was being taken to the Italian ambassador, however, the prison captain ordered him to be brought back. Upon his return to the prison, Maggi was strangled to death; he left behind many manuscripts on literary and military topics, some of which were published posthumously, including his two works penned in prison. TAWB

Della fortificatione delle città / di M. Girolamo Maggi, e del capitan Iacomo Castriotto, ingegniero del christianiss. re di Francia ; libri III. Venice: Camillo Borgominiero, 1584. Q. 623.1 M272d.

Graduate Architecture Students in Professor

Graduate Architecture Students in Professor