Curatorial intern Brian Flota has been searching the Library’s modern British literature holdings in order to track down items from the Tom Turner collection of British literature, purchased by Gordon Ray in the 1950s. In the process, Brian discovered many previously unknown association copies and a number of fine press poetry chapbooks. In this post, he picks ten of the items to share with the readers of Non Solus.

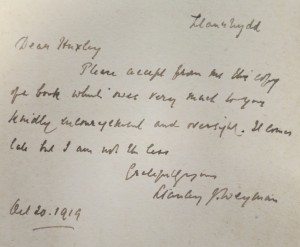

(1) Stanley J. Weyman. The Great House. London: John Murray, 1919. (823 W54gr 1919)

Stanley Weyman (1855-1928) is best known for his French historical romances, which were compared to Alexandre Dumas at the time of their publication. This late novel, The Great House, is about the anti-corn law movement. The library’s copy features an inscription from Weyman to Leonard Huxley (1860-1933), thanking him for his “kindly encouragement and oversight.” Leonard Huxley was the editor of the Cornhill Magazine, in which this work was originally serialized. He was also the father of the great English novelist Aldous Huxley (1894-1963).

(2) Ouida. “Held in Bondage,” or, Granville de Vigne: A Tale of the Day. London: Tinsley, Brothers, 1863. (823 D374he)

Ouida was the nom de plume of Maria Louise Ramé (1839-1908), a prolific English writer known primarily for her popular adventures and historical novels. Held in Bondage was her first novel, published in three volumes. The Library’s copy includes a four-page letter, handwritten and signed by Ouida, tipped-in the first volume. Ouida lived a tempestuous life filled with extravagances paid for by her best-selling novels, but died in poverty in Italy, surrounded by the many stray dogs she had adopted.

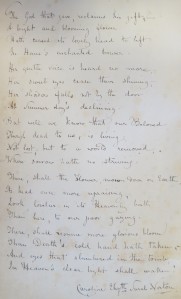

(3) Caroline Sheridan Norton. The Dream and Other Poems. London: Henry Colburn, 1840. (821 N82d)

The Dream was the sixth book of poetry published by Caroline Elizabeth Sarah Norton (1808-1877). A woman of high society, her life, especially during the time of the publication of The Dream, was fraught with public scandal. On the front fly-leaf of the Library’s copy, Norton has inscribed what appears to be an original, twenty-line poem, beginning, “The God that gave, reclaimed his gift; –.”

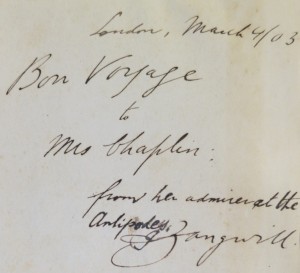

(4) Israel Zangwill. The Grey Wig: Stories and Novelettes. London: William Heinemann, 1903. (823 Z1gr)

Israel Zangwill (1864-1926) was a notable Jewish writer from England and an important member of the Zionist movement. Zangwill is most remembered today for his 1908 play The Melting Pot, which served to popularize the term and concept. Our copy of his earlier collection of short stories, The Grey Wig, features an inscription to “Mrs. Chaplin,” a relative of his wife, Edith Ayrton Zangwill. Edith Ayrton’s mother, Matilda Charlotte Chaplin Ayrton (1846-1883), was a member of the “Edinburgh Seven” – a group of women who fought unsuccessfully to earn medical degrees from Edinburgh University in the early 1870s.

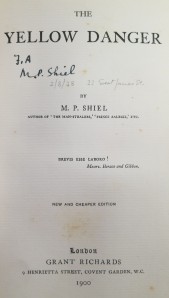

(5) M.P. Shiel. The Yellow Danger. London: Grant Richards, 1900. (823 Sh59y 1900)

M.P. Shiel (1865-1947), the English popular adventure and science fiction novelist, first published The Yellow Danger in 1898. This xenophobic novel of racial conflict was apparently an influence on Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu character. The library’s copy is inscribed by Shiel on the title page. Shiel’s popularity has waned greatly since his death, but his post-apocalyptic novel The Purple Cloud (1901) was recently republished by the University of Nebraska Press in their “Bison Frontiers of Imagination” series.

(6) Four Grant Richards Items:

Grant Richards. Caviare. London: Grant Richards, 1912. (823 R392c)

Grant Richards. Valentine. London: Grant Richards, 1913. (823 R392v)

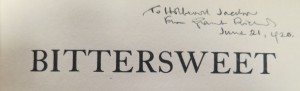

Grant Richards. Bittersweet. London: Grant Richards, 1915. (823 R392b)

William Watson. Lachrymae Musarum and Other Poems. London: Macmillan, 1892. (821 W33ℓ)

Grant Richards (1872-1948) was one of England’s most prominent publishers in the early 20th Century. As a publisher, he is perhaps most famous for publishing, after a decade-long delay, James Joyce’s first short story collection, Dubliners (1914). Richards was also a novelist. The library has three of his novels inscribed in a miniscule hand to journalist and bibliophile Holbrook Jackson (1874-1948). And the library also owns a book inscribed to Grant Richards: a slim hardbound volume of poetry by William Watson (1858-1935) that is inscribed to Richards from “his sincere friend.” If you are interested in Grant Richards’s writings or in his work as a publisher, the Rare Book & Manuscript Library holds a collection of his correspondence, literary manuscripts, and business papers. Additional collections of Grant Richards materials are housed at Georgetown University, the Library of Congress, the National Library of Ireland, and Princeton University.

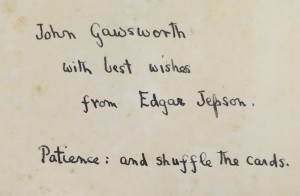

(7) Edgar Jepson. The Passion for Romance. London: H. Henry & Co., 1896. (823 J46pa)

Edgar Jepson (1863-1938) inscribed this copy of The Passion for Romance to his sometime literary collaborator John Gawsworth (1912-1970), later known in his own right as a poet and a publisher. Gawsworth was also M.P. Shiel’s bibliographer and literary executor. In the inscription in the Library’s copy, Jepson provides some advice for Gawsworth: “Patience: and shuffle the cards.”

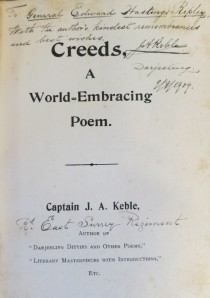

(8) Captain J.A. Kemble. Creeds: A World-Embracing Poem. [Calcutta, India: s.n., 1909?]. (821 K232c)

Not much is known about J.A. Keble, but this copy of his poem Creeds is an interesting artifact of Great Britain’s colonization of India. The poem is inscribed to one “General Edward Hastings Ripley” from Capt. Keble’s station in Darjeeling. A publisher’s advertisement affixed to the verso of the author’s portrait notes he is also the author of Darjeeling Ditties and Other Poems.

(9) Thom Gunn. The Garden of the Gods. Cambridge, Mass.: Pym-Randall Press, 1968. (821 G956ga)

Thom Gunn (1929-2004) was part of the British school of writers that produced Philip Larkin, Kingsley Amis, and Ted Hughes. Interestingly, he relocated to the San Francisco Bay Area in 1954 and was present for the emergence of the Beat Movement there. This chapbook of his poem “The Garden of the Gods” is signed and numbered by the author.

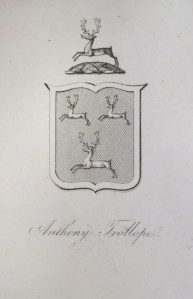

(10) Thomas Adolphus Trollope. A Peep Behind the Scenes at Rome. London: Chatto and Windus, 1877. (823 T746p)

Unlike the other items discussed in the post, A Peep Behind the Scenes at Rome is not signed by its author, who in this case happens to be Thomas Adolphus Trollope (1810-1892). Thomas Adolphus Trollope was a noted travel writer and older brother to the Victorian novelist Anthony Trollope. What makes the copy noteworthy is Anthony Trollope’s armorial bookplate on the front paste-down. This copy was subsequently passed down to Anthony’s granddaughter, Muriel Trollope. The Rare Book & Manuscript Library holds a small collection of the letters, journals, unpublished literary works of Anthony Trollope and other members of the Trollope family, including some of Thomas Adolphus Trollope’s letters and journals. BF, AD